Somalia

Back to the drawing board

Africa Confidential

June 03, 1994

A new battle is looming in Somalia. This time it is a constitutional one between proponents of centralism and federalism. The need for a centralised state was one of the few issues that the United Nations Operation in Somalia (Unosom) agreed on with General Mohamed Farah ‘Aydeed’ in the midst of their war last year. But Aydeed’s great rival, Ali Mahdi Mohamed, and some of his allies - notably the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) - were less certain about the state. Unosom’s failure, and a widespread de facto acceptance of regionalism (growing out of the numerous clan factions refusing to accept higher authorities) has led to growing support for alternatives to a centralised state.

A federal solution is finding favour in some quarters. Abdurahman Tour, the first President of ‘Somaliland’ (which declared itself independent in May 1991 but has not been internationally recognised) now enthuses about the federal option, having been a strong defender of a centralized state in an independent northern Somalia. Tour’s change of heart is certainly connected to the fact that he was ousted last year.

However, other groups of Somali intellectuals, as well as United States officials, have been trying to map out what a federal state would look like. Though the latest is from the Majerteen, one of the five clans in the Darod clan family, it makes a serious effort to address some of the claims of the other major families: the lsaaq in Somaliland and the Hawiye, Rahenweyne and Digil in the centre. Equally, it still suffers from what many Somalis see as Darod attempts to perpetuate their control, either directly or regionally. Gen. Mohamed Siad Barre, president of Somalia 1969-91, was from the Marehan, a Darod clan; the leading clan in the civilian governments of the first nine years of independence, 1960- 69, was the Majerteen.

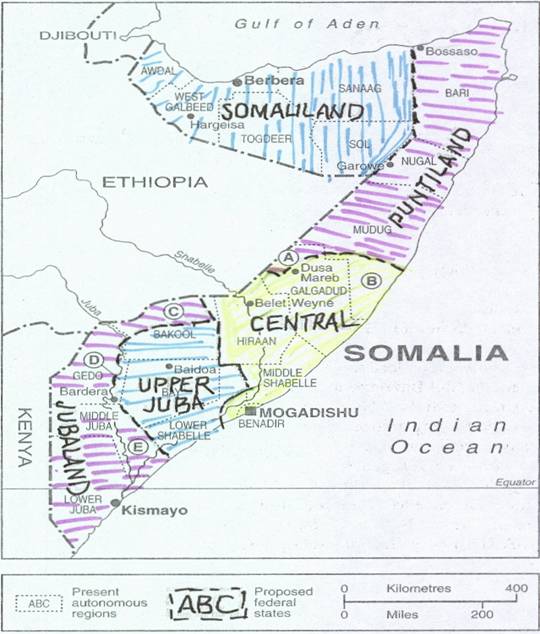

US interest in federalism for the region dates back to 1990 (AC Vol 31 No 25). The original UN plans for intervention in Somalia in 1992 were organised around a concept of four regions, each having a port where troops and aid could be deployed. These were Kismayo for the south-west; Mogadishu for the centre; Bosasso for the north-east and Berbera, north-west. The UN ignored the north-west’s May 1991 declaration of independence and made little or no attempt to accommodate any territorial or historic claims by clans.

This contrasted with Unosom, headed by Admiral Jonathan Howe, which in 1993 oscillated between unsuccessful attempts to organise national unification through political conferences in Addis Ababa (January, March and December) and efforts to alter the balance of power by capturing Aydeed and militarily defeating his Hawiye dominated Somali National Alliance (SNA). None of the meetings achieved more than temporary agreements between the main protagonists and, at the UN Humanitarian Conference on Somalia in Addis Ababa on 29 November – 1December 1993, donors made it clear they would probably target future aid on areas with stable administrative structures, where there was some degree of certainty that it would not be seized by bandits or clan militias.

Towards the end of 1993, the US State Department sent a map outlining possible federal boundaries to a number of prominent Somalis for comment. It was made clear this was intended as no more than a draft and could be changed to accommodate difficulties. While the US map had links with the UN’s regional approach, it made important changes to this on the basis of clan claims. Most significantly, it suggested an enlarged north-east to incorporate the Darod clans in Somaliland and broke up the large south-west region to provide one large region for the Rahenweyne and Digil but allowing the Darod to the west of Juba (and in the northern part of Bakool region) their own status. Neither the Isaaq, Somaliland’s biggest clan, nor the Hawiye, in Mogadishu and the centre, found this acceptable. It was promptly condemned as a ‘Darod’ map. One Hawiye response was to produce their own map, which accepted the idea of a Rahenweyne region but proposed a greatly enlarged Hawiye area in the centre, taking in the whole of Mudug region, in which both Hawiye and Majerteen (Darod) live. This, of course, was unacceptable to the Darod.

Now the Majerteen have responded with this latest version (seeMap). This is likely to be discussed at the SSDF’s Fifth Congress, due to start on 25 June, when there is every likelihood that a regional government will be announced. The SSDF is the largely Majerteen faction which controls north-east Somalia, named Puntiland on the map. This. rather implausibly, harks back to the Land of Punt, visited by Egyptians over 3,000 years ago. This Majerteen map again is clan-based but makes greater efforts to accommodate the claims of non-Darod clans and organisations. It accepts a continued existence for Somaliland, preferably as a region rather than an independent state and, in contrast to the US map, includes the Darod clans in the regions of Sool and Sanaag, as well as the Dolbuhunta and Warsengeli. It also allows the Rahenweyne a large region, including some areas across the Juba River. But it raises other problems:

1- It is still likely to be seen as another Darod effort as it makes controversial increases to two substantial Darod regions. Puntiland as shown includes the areas of Mudug inhabited by Darod (marked ‘A’). while putting the areas inhabited by Hawiye (B) into the Central state. Yet the Hawiye. and in particular the HabrGidir (the Hawiye sub-clan from which Aydeed comes) would claim a great deal more of Mudug.

2. The Rahenweyne would resist letting the north of Bakool Region (C) go: they would also expect a great deal more of the trans-Juba area than section D. Until they were forced out by the Marehan during Siad Barre’s time. the Rahenweyne inhabited both sides of the Juba in Gedo Region.

3. Also highly controversial is the proposed position of Jubaland, seen on this map as a Darod state but incorporating substantial areas inhabited by various other clans, particularly area F. which includes Hawiye, Rahenweyne and Dir as well as ‘Bantu’ clans - agriculturalists of slave descent, who are also beginning to flex their political muscles.

4. The major problem with the map, as with all similar documents. is that it takes insufficient account of the conflicts within clan families. The Hawiye as a whole have no love for the Darod but the major conflict in the centre and Mogadishu is between Hawiye sub- clans, the Abgal and the Habr Gidir (which are themselves not entirely united). Similarly, while the Darod see the Hawiye as their main enemy, the problems of Kismayo and Jubaland relate most to divisions within the Darod and the desire of the Mohammed Zubeir/Ogaden to take control of Kismayo which, like Mogadishu, is a relatively wealthy urban centre.

Nor does such a map take into account those politicians and faction leaders, prominent among them Aydeed and the SSDF military commander, Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf, who believe strongly in a centralised approach to government. This map represents an intellectual approach which overlooks some unpalatable political realities: it allows for flexibility but relies on qualities that have been in short supply for a long time in Somalia, such as an overwhelming desire for peace and a willingness to compromise •